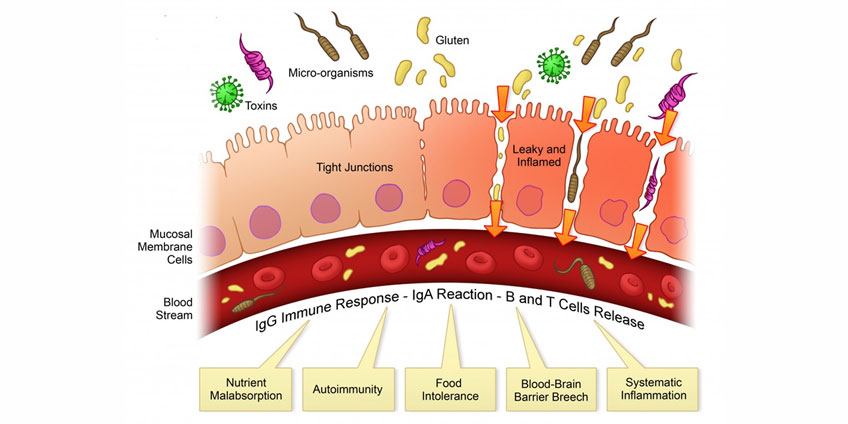

Your digestive tract is essentially a long, hollow tube running from one end of your body to the other. Up to 80% of your immune system is found in your digestive tract!

The lining of the gut is armed with immune cells. It is designed to protect the body from parasites, bacteria, and yeast that you may pick up from food or your environment.

A toxic and unhealthy liver is common in those with leaky gut and bacterial overgrowth.

But what happens when this system fails?

As it turns out, the lining of the digestive tract is not the only place where the immune system is on high alert for unwanted guests. The gut is your first line of defense.

Your second line of defense is your liver.

When harmful bacteria, dietary irritants, and environmental toxins get past the gut lining, they drain into the liver.

Your ability to cleanse depends directly on the health of your gut and your liver. To support efficient detoxification and transformation in the liver, a sealed, balanced gut is key.

The liver is not so much of a filter as it is a place where detoxification and transformation happen. With the help of powerful antioxidants like glutathione, the liver transforms toxins. And with the help of the immune system, the liver clears potentially harmful substances—including bacteria and pro-inflammatory fragments of bacteria.

The liver is a major immune organ. (2) And most of the liver’s immune cells are found around the portal vein, which shuttles nutrient-rich blood from the gut and into the liver.

In fact, bacteria can even be cultured (or collected and grown) from around the portal vein. (3)

As you can imagine, a gut that is inflamed and leaky means more work for the liver. When your inner ecosystem is out of balance, the liver has a difficult time keeping up with the body’s demands.

Your Inner Ecosystem and Leaky Gut

The inner ecosystem of your digestive tract is designed to protect your body from outsiders. Stomach acid, the wave-like motion of the intestines, and immune cells tucked into the lining of the intestines all work together to prevent leaky gut.

So, what ultimately causes leaky gut?

- Bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine, which can be the result of enzyme deficiency, stress, or weak stomach acid.

- Candida overgrowth

- Food poisoning; many bacteria are equipped with poisons that destroy the lining of the gut.

- Parasites

- Use of alcohol and NSAIDs

- Many medications

- Chronically elevated cortisol levels. (Stress hormones)

- Food irritants and allergies. ie gluten, dairy, genetic food allergies

- Chemicals found in packaged and prepared foods.

Along the intestines—especially the large intestine—there are communities of bacteria and yeast that work with your body. These beneficial bacteria and yeast nourish you. They also help protect you from outside toxins and disease-causing microorganisms. Remember, the gut is your first line of defense.

Leaky Gut and an Overworked Liver

An inner ecosystem that is out of balance is one where bacteria and yeast have grown out of control. The intestinal wall becomes inflamed. Bacteria and fragments of bacteria are able to slip past the gut wall and drain into the liver.

This is bad news for the liver.

Researchers have found that a toxic and unhealthy liver is common in those with leaky gut and bacterial overgrowth. (4)(5) Other research shows that the progression of liver disease is driven by leaky gut. (6) A constant rush of bacteria, bacteria fragments, and outside irritants into the liver can overwhelm the liver’s ability to clear these toxins.

The danger of a leaky gut does not end with an overworked liver. With time, a wounded inner ecosystem may even stimulate fibrosis (or injury) of liver tissue. Once this happens, the entire body is at risk for disease, infection, and Candida overgrowth. (7)

30%-50% of those with liver cirrhosis—or extreme liver damage—succumb to the systemic effects of circulating bacteria and fragments of bacteria. (8)(9) Other studies show that those with end-stage liver damage also have leaky gut. (10)

How to Support the Liver

Once bacteria, yeast, or outside toxins get past the liver, their ability to pollute the body is unchecked. As these pollutants circulate, the liver diligently attempts to get rid of both circulating waste and new irritants draining into the liver from a leaky gut.

It is a vicious cycle. The first step to breaking the cycle is to heal the gut.

In order for the body to properly cleanse, your inner ecosystem must be healthy and balanced. Some of the best support that you can give to yourself and to your liver is to make sure that the lining of your gut is sealed.

The literature showing a link between extreme liver damage, toxicity, and leaky gut is staggering. For example, studies have shown that those with non-alcoholic liver disease also have a leaky and inflamed gut. (11)(12) Cases of hepatitis C and extreme liver damage from years of alcoholism both occur with bacterial overgrowth in the intestines. (13)(14)

One study published in Hepatology in 2003 found that probiotics were able to reduce inflammation in the liver tissue of mice with fatty liver disease. (15) In other words, heal the gut—and you can optimize the health of your liver and thus your ability to cleanse.

The beneficial bacteria that you will find in fermented foods or probiotic beverages can nurture a hearty inner ecosystem. Good bacteria repair intestinal damage and reduce inflammation or “leakiness”.

How well you remove pollutants from your body is not solely dependent on your liver—much hinges on the integrity of your gut. With a healthy inner ecosystem, you can heal liver damage, restore your liver’s ability to cleanse, and deepen your detox.

Call our office today to get started on restoring your gut lining and detoxifying your liver.

REFERENCES:

1. Minocha, A. Probiotics for preventive health. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 2009; 24(2), 227-241.

2. Gao B, Jeong WI, Tian Z. Liver: An organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology 2008; 47: 729-736

3. Singh R, Bullard J, Kalra M, Assefa S, Kaul AK, et al. Status of bacterial colonization, Toll-like receptor expression and nuclear factor-␣B activation in normal and diseased human livers. Clin Immunol. 2011; 138:41–49.

4. Bauer TM, Schwacha H, Steinbruckner B, Brinkmann FE, Ditzen AK, Aponte JJ, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in human cirrhosis is associated with systemic endotoxemia. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97: 2364–2370.

5. Jun DW, Kim KT, Lee OY, Chae JD, Son BK, Kim SH, et al. Association between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and peripheral bacterial DNA in cirrhotic patients. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:1465–1471.

6. Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med 2007;13:1324–1332.

7. Ruiz AG, Casafont F, Crespo J, Cayon A, Mayorga M, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein plasma levels and liver TNF-␣ gene expression in obese patients: evidence for the potential role of endotoxin in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Obes Surg. 2007; 17:1374–80.

8. Christou L, Pappas G, Falagas ME. Bacterial infection-related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1510–1517.

9. Wong F, Bernardi M, Balk R, Christman B, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. Sepsis in cirrhosis: report on the 7th meeting of the International Ascites Club. Gut 2005;54:718–725.

10. Thalheimer U, De Iorio F, Capra F, del Mar Lleo M, Zuliani V, et al. Altered intestinal function precedes the appearance of bacterial DNA in serum and ascites in patients with cirrhosis: a pilot study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 22:1228–34.

11. Abu-Shanab A, Quigley EM. The role of the gut microbiota in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 7:691–701.

12. Pappo I, Becovier H, Berry EM, Freund HR. Polymyxin B reduces cecal flora, TNF production and hepatic steatosis during total parenteral nutrition in the rat. J Surg Res. 1991; 51:106–12.

13. Sandler NG, Koh C, Roque A, Eccleston JL, Siegel RB, Demino M, et al. Host response to translocated microbial products predicts outcomes of patients with HBV or HCV infection. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1220–1230, 1230. e1221–1223.

14. Morencos FC, De las Heras Castano G, Martin Ramos L, Lopez Arias MJ, Ledesma F, Pons Romero F. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:1252–1256.

15. Li Z, Yang S, Lin H, Huang J, Watkins PA, et al. Probiotics and antibodies to TNF inhibit inflammatory activity and improve nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2003; 37:343– 50.